'Water Activity'... the Misunderstood Food Safety Algorithm

It's not the ingredient. It's what you do with or to the ingredient that determines the number of bugs in your goodies!

Recently, a member of my Cottage Food Business Facebook community, posted about pumkin, wondering:

“I’ve seen people selling pumpkin bread, but can’t sell pumpkin pie?”

Canned pumpkin is canned pumpkin, right? What is the big deal?

Along with temperature and pH (stands for “power of Hydrogen”), water activity is often THE major food safety measurement useful for our industry, especially for bakers. And you may not even know what it is, what it’s for, or why it’s important.

Water Activity, indicated by the symbol “Aw” (not a root beer company), is a critical piece of food quality and associated shelf life.

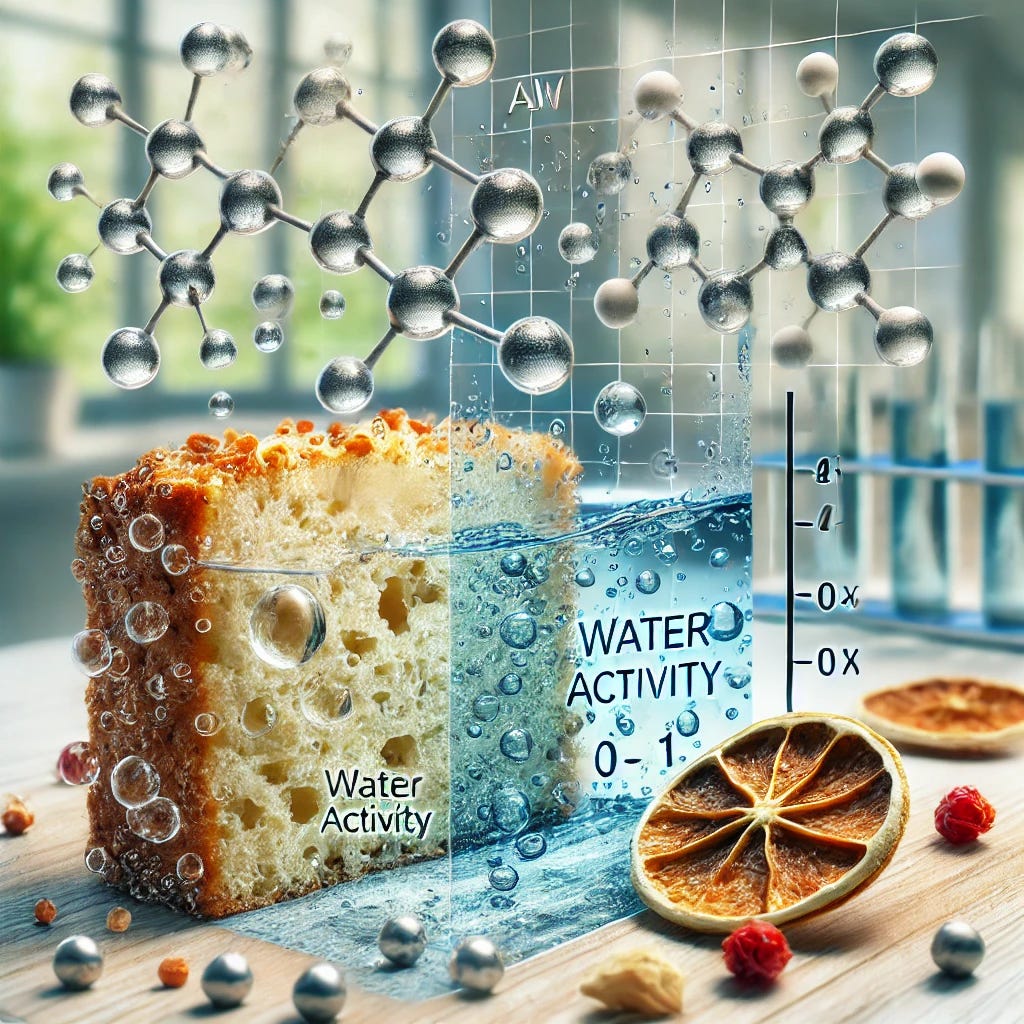

As you know, moisture is very conducive to the growth of any number of good (e.g. fermenting) and bad organisms. In our industry, we are worried about the bad. Some of those guys (certain bacteria, molds, etc.) can make you sick or even put you into the ground.

Aw is measured from 0.0 to 1.0, with zero being bone dry, and 1.0 being pure water.

Stick your finger into a pumpkin bread to check for dryness. Then do the same with a pumpkin pie. Which one (obviously) possesses a higher water content?

Somewhere in between bread and pie, there is a measurable threshold between 0 and 1, that got crossed in the preparation, even though both came out of the oven.

So if we do a test with a water activity meter or hygrometer, what is the Aw number where we need to be concerned? What is the statutory level?

A water activity (Aw) level of 0.85 or below is generally considered safe. Meaning foods below this level are not considered potentially hazardous and are less likely to support the growth of harmful bacteria.

I’ve seen some states that require Aw to be even lower. But at least now we are in the relevant range. An Aw of 0.85 might even seem high! But foods without a significant moisture content may not be worth eating. So we allow it as high as we can, while maintaining protection.

Besides the high pH of fruits and betters, low water activity is a big reason jams are allowed in cottage foods, while many fruity products are questionable.

Did you know that to legally call a product “jam”, it needs to contain at least 60% “sugar” (natural and added combined)? This is measured in “Brix” units, with an inexpensive tool called a “refractometer”. The sugar content “binds” the water, keeping your sweet preservative below 0.85.

If you do jams, you might consider picking one up. They’ve come way down in price over the past 20 years. Here is a link to the one I recommend: REFRACTOMETER

What we are really talking about here, is what our industry calls TCS (Time-temperature Controlled for Safety) foods. The most discussed types of ingredients in this category are dairy products, especially as used in a buttercream frosting products.

Buttercream is used by a high percentage of cottage bakers, on a lot of products. And finding the right “recipe” that can be cottage approved, while working around “no TCS”, is a major challenge.

Another major category is fruit and/or vegetable products baked into or onto a goodie. Fresh veggies (and some fruits) are especially a concern because they are naturally alkaline. Meeting a pH threshold is probably not going to happen, so Aw is all you got.

PS Bananas are the only major alkaline fruit… does your state OK banana bread? Most do, but I am sure food safety crosses their mind.

Why the controversy?

A state government developing cottage food rules usually decides that home preparation is probably not enough to guarantee safe Aw levels for finished goods in a TCS category. So they outlaw it as a cottage food ingredient.

(Although that is changing as some states now allow TCS under certain conditions.)

Depending on the state (and maybe the inspector), outlawed TCS ingredients are sometimes approved - if, and only if - you get separate independent testing… which may or may not be offered via your inspection agency.

So, the final say is always from the mouth of your food inspection folks. Pin them down as to whether TCS foods can or can’t be approved with testing (and if so, a list of testing labs.) Sometimes they can refer you to approved recipes.

And it’s a good idea to network with those folks anyway. A friendly relationship may help you out down the road, for any number of reasons.

Best wishes, and be food safe out there!

Mal Dell

The MONETIZATION CHEF

”Helping Foodies Cook Up Profits!”